By Greg Ip

May 10, 2023

Last fall, Americans were obsessed with inflation. The issue dominated the midterm elections. One in five respondents called it the nation’s most important problem, according to Gallup.

Consumer prices rose 4.9% in the year through April, the lowest in two years. PHOTO: BRANDON BELL/GETTY IMAGES

These days, their attention is elsewhere. Just 9% of Gallup respondents now call inflation the most important problem, behind government leadership and the “economy in general” and just ahead of immigration and guns. It has barely come up in Washington’s fight over raising the debt ceiling.

Good news? Maybe not. It may mean people are getting used to higher inflation, which would be very bad news. The more people behave as if high inflation is here to stay, the likelier it is to stay. That would force the Federal Reserve to choose between inducing a potentially deep recession to force inflation lower, or giving up on its 2% inflation target.

The Labor Department reported Wednesday that consumer prices rose 4.9% in the year through April, the lowest in two years and down substantially from 9.1% last June, mostly because gasoline prices have fallen. That drop helps explain why people aren’t obsessing as much over inflation, though they are still obsessing more than before the pandemic.

And yet inflation is very much still a problem. Core inflation, which excludes food and energy, is a better predictor than overall inflation of underlying price trends. Core inflation was 5.5% in April, down from 5.6% in March. On a monthly basis, core prices rose 0.4%, equivalent to 5% at an annual rate, in line with the past four months. Excluding shelter, core services prices, which the Fed watches closely, rose a much more tame 0.1% for the month, according to independent analyst Omair Sharif. Wages, which strongly influence service prices, grew 4% to 5% through the first four months of the year, too high to be consistent with 2% inflation.

The original surge in inflation had two main sources: pandemic and war-related disruptions to the supply of goods, services and labor, and federal stimulus and near-zero interest rates that stoked demand.

Those factors have largely receded. Supply chains are functioning normally. Labor supply has mostly recovered, with the labor-force participation rate now in line with its prepandemic trend. Gasoline prices are back to where they were before Russia invaded Ukraine. As for demand, fiscal stimulus has expired, and since March 2022 the Fed has raised its short-term interest-rate target from near zero to between 5% and 5.25%.

The theory two years ago was that once these transitory supply and demand factors receded, inflation would return to 2%. And indeed, some prices have fallen, apartment rents are rising more slowly and employers aren’t so desperate to hire.

But this theory always carried a caveat: the longer it took for these transitory factors to subside, the greater the risk people would adjust to faster rising prices and wages which might make them self-sustaining. That may be under way now.

“We’re getting a process where persistent, large shocks to inflation are starting to get embedded in price and wage setting,” said Bruce Kasman, chief economist at JPMorgan Chase. “Even though energy prices have come down and growth isn’t robust, pricing power and profit margins have been stronger than expected.”

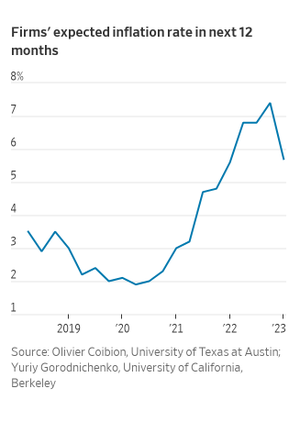

Price- and wage-setting psychology is often inferred from expectations of future inflation. Fed officials comfort themselves by noting long-run expectations, i.e. five to 10 years from now, are still near 2%.

But central bankers’ belief that long-term expectations predict behavior better than short-term expectations rests on weak empirical foundations. If they are wrong, then it is ominous that the University of Michigan reports consumers’ one-year expectation has been above 4% almost continuously for two years. Firms, which actually set prices, also expect inflation above 5% in the coming year, according to a survey by economists Olivier Coibion and Yuriy Gorodnichenko.

In earnings reports, companies complain a lot less about input costs or labor shortages; they do report effortlessly raising prices. The new buzzword among chief financial officers is “elasticity”: how sensitive sales volume is to price increases. The less sensitive, the better for companies. “Our elasticities remain favorable on an aggregate basis,” Procter & Gamble Chief Financial Officer Andre Schulten said last month, describing a quarter in which the company’s sales volume dropped 3% from a year earlier while it raised prices about 10%.

“When Coca-Cola, Pepsi, Kimberly-Clark, Kraft Heinz, and Conagra are raising prices, that filters through to restaurants, and when you have Hilton and Marriott talking about average daily revenue going up, that translates into services” inflation, said Samuel Rines, strategist for market advisory Corbu. “That is going to continue until the consumer pushes back.”

He said consumers are assuming if prices are going up, so are their wages. “Until that assumption is broken, the consumer is not going to blink at paying an extra 5% or 6% extra on ketchup.”

Some policy makers say companies are worsening inflation by boosting profits. But if that was once true, it no longer is; Riccardo Trezzi of Underlying Inflation, a research service, calculates that, based on government data, profits’ contribution to prices declined in the fourth quarter.

Anyway, whether wages are driving prices or vice versa may soon be irrelevant. Once inflation has settled at a higher steady-state rate, wages and prices rise together.

In such a situation, it can take a deep recession to get inflation down. This seems to be why markets think inflation will drop sharply in the coming year and the Fed will start to cut interest rates. Yet thus far there is no evidence of even a mild recession. Housing, the sector most sensitive to more expensive credit, has stabilized and construction employment is rising.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell says slow economic growth, not a recession, should be enough to return inflation to 2%. For now, the central bank has signaled it may have finished raising rates.

Central bankers seem wedded to gradualism—accepting a very slow fall in inflation to avoid too much damage to the labor market, Mr. Kasman said.

The problem with gradualism is that the longer the path for lowering inflation, the less likely it is to happen.

Write to Greg Ip at greg.ip@wsj.com

Dow Jones & Company, Inc.